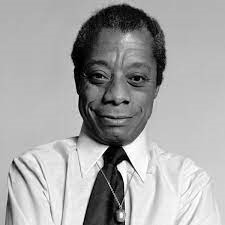

Guerra & Partners Spotlights James Baldwin In Celebration Of Black History Month

|

|

We officially began celebrating Black History Month in the United States in 1986, when Congress passed Public Law 99-244 designating February 1986 as National Black History Month. It is as important now, as it was then, to highlight the history and contributions of African Americans because African American history is American history.

This month, we highlight James Baldwin (1924-1987)—an extraordinary author and civil rights and gay activist. Some, however, never considered Baldwin to be an activist but a narrator of the times and sentiments of people of color. Indeed, Baldwin recognized the inherent conflict of being a writer and activist. To Baldwin, an activist’s role was to simplify issues and facts to appeal to broad audiences, which meant that the activist had to sometimes maintain private points of view and adjust his message in response to public sentiments. A novelist, however, had to remain faithful to the complexities of life to create a true image. Baldwin confronted this conflict and elected to center truth in his works and activism: “I always felt that when I was talking publicly, I was talking mainly to the children, to the young, which is to say to the future, and I was talking about people’s souls; I was never really talking about simply political action, because I am not a political activist.”

Baldwin was a prolific writer of semiautobiographical novels, plays, poetry, and essays centering on race, politics, and sexuality. His novels and plays were central to the civil rights movement and helped raise new awareness of racial and sexual oppression. Born in Harlem, NY in 1924, Baldwin was the son of a domestic worker and never knew his dad. At three years old, his mother married a factory worker and storefront preacher, who was hard and cruel and eventually died in a mental hospital. Baldwin lived his early years in extreme poverty but was a voracious reader and writer who published his first story in a church newspaper at 12 years old.

At 17, Baldwin turned away from the church, where he was active as a preacher, and moved to Greenwich Village to study at The New School. He continued writing and publishing short stories, essays, and book reviews while in college. In 1948, Baldwin, like many other African American artists during the civil rights era, moved to Paris, France because he felt the racial injustices in America were too much to bear. He noted of his experiences abroad, “Once you find yourself in another civilization … you’re forced to examine your own.” Baldwin’s travels appeared to bring him even closer to the social concerns and unrest in America.

In 1953, Baldwin published his first novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain, a semiautobiographical work about his experience as a young, black preacher in a revivalist church in his early teens. Baldwin’s second novel, Giovanni’s Room, was published in 1956 and dealt explicitly with homosexuality. Baldwin’s publisher tried to dissuade him from publishing Giovanni’s Room, advising that it would ruin his reputation. But Baldwin insisted on telling his truth. Baldwin’s next two novels, Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, were no less revealing of Baldwin’s experiences. They featured black, white, heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual characters, and were saturated with a sense of violent unrest and outrage—indicative of the turbulence of the 1960s. Another Country became an immediate bestseller. Baldwin also wrote many essays about his thoughts on race in America and calling for equality, publishing four collections of his essays in the 1950s and 1960s—several of which also became bestsellers.

Overwhelmed by a sense of responsibility, Baldwin returned to America to participate in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Baldwin traveled throughout the American South delivering speeches to all who would listen to his thoughts on the plight of African Americans and his ideology for achieving meaningful change. Baldwin’s ideology was a mix of the “flexed muscle” approach of Malcolm X and the nonviolent approach of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. As he traveled throughout the South, Baldwin also wrote and published The Fire Next Time, described as an incendiary and explosive work about black identity and the state of racial unrest in America. This, too, became an instant bestseller and landed Baldwin on the cover of TIME Magazine.

Once again overwhelmed with American’s racial disparities after the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, Baldwin returned to France, where he wrote and published If Beale Street Could Talk in 1974. This work encapsulated Baldwin’s own disillusionment and that of the times, and many described it as harsh and bitter, although he remained a constant advocate for universal love and brotherhood.

During the last 10 years of his life, Baldwin continued to produce important works of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and essays about race and his experience as a gay black man. He also taught at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and Hampshire College to connect with young people. Baldwin died in 1987 after a long battle with lung cancer. By his death, Baldwin had become one of the most important and vocal advocates of equality. His commitment to accurately sharing his life, thoughts, and experiences about race and sexuality continues to resonate with millions of Americans and his works will remain an essential part of the American canon.

This month – and every month – we salute James Baldwin and honor his contributions to American art and history.

Sources:

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-history-that-james-baldwin-wanted-america-to-see

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2935113

https://nmaahc.si.edu/james-baldwin

http://www.myblackhistory.net/James_Baldwin.htm

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/james-baldwin-about-the-author/59/#

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/05/t-magazine/james-baldwin-giovannis-room.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-12-01-mn-26007-story.html